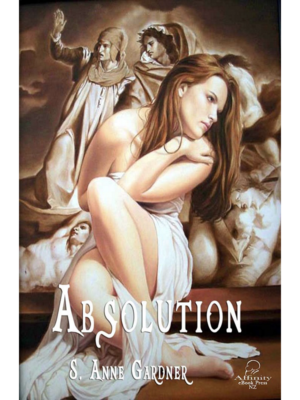

Description

Follow the adventures of Rhodes Scholar Jeri O’Donnell who becomes embroiled in Ulster’s fight for independence from Britain. Later Jeri travels through the Himalayan highlands where she meets Kelly Corcoran, a tourist from the United States. Kelly is willing to gamble her heart, as Jeri struggles against involving anyone in her perilous and chaotic life.

In an epic siege largely ignored by the wider world, Kelly, who was prepared to give up comforts and certainties when she became part of Jeri’s nomadic life, encounters more than physical danger. Her ability to maintain her core integrity is assaulted by the inevitable ugliness of war. For Jeri, the true battle is confronting her attraction to violence as she struggles against losing herself in the exhilaration of combat.

Rebellion in Ulster

During a visit to relatives in Northern Ireland, Rhodes Scholar Jeri O’Donnell’s plans for a scholarly life are shattered by a tragedy that kills her beloved cousin, Fiona, and sends Jeri to Armagh Women’s Prison. In Armagh, IRA volunteer Jill Leary attempts to recruit the young American to Ulster’s fight for independence from Britain, while the mysterious Arkadia O’Malley seeks nothing less than Jeri’s soul.

When Jeri is released as precipitously as she was imprisoned, she chooses to embrace Ulster’s struggle as her own and joins the Provisional IRA. Jeri is sent out of Northern Ireland to be trained, first to the Irish Republic and then to Eastern Europe. Cool under pressure and fierce in action, she becomes the ideal urban soldier whether in Rotterdam, Belgrade, or Belfast.

Attracting women has never been difficult for the intense young woman from Southie, Boston’s Irish neighborhood, but Jeri’s remorse following Fiona’s death makes intimacy virtually impossible. Several women try to reach her, but the violence of her life only drives Jeri further from human comfort. Although she can never quit questioning the morality of her actions, Jeri has a taste for fighting that she once hoped to leave behind in the streets of Southie. Then a bomb explodes and the resulting carnage plunges Jeri into a despair that forces her to reconsider what choices, if any, are left to her.

Rendezvous in the Himalaya

Haunted by memories of the disastrous Troubles of Northern Ireland, Jeri O’Donnell has joined forces with her old friend, Rafi Gregoric, who is a power broker in the new Russia. Their current venture is arranging a meeting between a Tibetan monk and a distinguished UN official. The monk has evidence of brutal Chinese oppression that may enable the reforms that swept the soviet Union to reach China. Guiding the UN official through Himalayan highlands is exactly the kind of work Jeri needs to exercise her skills and exorcise her conscience.

Just as the mountain trek begins, Jeri encounters Kelly Corcoran, a tourist for the United States. Kelly is adrift in Nepal, emotionally desolated by the recent loss of her brother and his friends to AIDS. Both women recognize that a powerful connection links them, but while Kelly is willing to gamble her heart, Jeri struggles against involving anyone in her perilous and chaotic life.

An uneasy compromise finds Kelly accompanying the small group at least to the Tibetan border. On this perilous expedition, Kelly will need every ounce of her courage and nerve to convince Jeri that the future only makes sense if they are willing to risk it together

Requiem for Vukovar

Requiem for Vukovar continues the Refraction series and the exploits of Jeri O’Donnell and her partner, Kelly Corcoran.

Summer, 1991: Europe stands on the verge of its most violent crisis since World War II. Yugoslavia is crumbling and two of its republics, Croatia and Serbia, are reverting to an historic hostility. Aware of the gathering storm, Jeri agrees to escort Alenka, the sister of a friend, away from Vukovar, a small Croatian city.

Jeri plots a course that ought to be a quick drive, but instead, plunges them into a civil war, and they find themselves afoot with other fleeing refugees. Kelly and Jeri finally reach their destination only to find that Alenka is reluctant to leave her home and friends. Too soon, the avenues of their escape shut down.

In an epic siege largely ignored by the wider world, Kelly, who was prepared to give up comforts and certainties when she became part of Jeri’s nomadic life, encounters more than physical danger. Her ability to maintain her core integrity is assaulted by the inevitable ugliness of war. For Jeri, the true battle is confronting her attraction to violence as she struggles against losing herself in the exhilaration of combat.

Chapter 1

Chapter One

“Would you look at the new one, Rosie.”

Rosie looked across the prison dining room. The “new one,” as easy to find as a black sheep in a flock of white woolies, had placed her tray on an empty table.

“Setting herself off like that, Liz, I’m betting she’ll not last long.”

“She won’t have much choice, will she? I heard a rumor says she’s here for running guns. An American gunrunner.”

“A Yank. Oh well, then.” Rosie’s tone carried a world of attitude. “We don’t get much of that in Armagh.”

The gray-haired woman sitting near Rosie and Liz permitted herself a brief smile. In the perpetual murk of prison boredom, these two could occasionally amuse Arkadia O’Malley; she, however, was almost invisible to the younger women. Far from young but not yet old, O’Malley had been at Armagh Prison when they arrived and she was likely to be there when they left.

Arkadia O’Malley looked past the empty table between to the new arrival. She saw a very young woman who might be pretty behind the dark hair that partially obscured her down-turned face. A tray with a plate and a drink sat in front of her but she only stared at her food, apparently disinclined to eat. O’Malley had the impression that the newcomer was actually absent, as if she had somehow managed to leave her body behind and escape. Drugs, probably, and that would be the reason she was here. A gunrunner would be IRA, and the Rah prisoners kept to themselves. Since the newcomer was in with the general population, her offense was more likely drug smuggling. She certainly appeared downed out on something. Then again, just the reality of arriving in prison could send a woman into shock. The body searches were the worst, but the whole process of becoming incarcerated was designed to make the new prisoner aware that she was being severed from her previous life.

As if on cue to clear up the mystery, Jill Leary entered the dining room. Leary was in her late twenties, a woman of pleasant appearance with ash blond hair and the delicate, doll-like features that were pretty enough but long since gone out of fashion. All the women in the dining room watched as Leary, walking with as much authority as if she herself was a prison official, threaded her way among the tables and sat down across the table from the American. Anything unusual was a fascinating distraction to the women watching, but the presence of the IRA Section Commander, second only to Mairead Farrell herself, talking to a newly inducted prisoner in the general population dining room, that was well out of the ordinary.

“Tiocfaidh ar lá.”

The new prisoner continued to stare at her food.

“That means ‘our day will come’ in Irish.”

O’Malley was close enough to hear Leary translate her own greeting. She wasn’t close enough to hear the reply, but she thought the words were all Irish.

“At least there’s nothing wrong with your hearing, Geraldine O’Donnell,” Leary said. “I’ll tell the screws that you belong with us.”

The newcomer raised her head and fixed Leary with a gaze that was full of agony. “I’m not one of you.”

That was the first full view that Arkadia O’Malley had of Geraldine O’Donnell, and the sight elicited a startled shock of recognition despite the fact that she had never seen the young woman before. Shock lasted only an instant and then vanished, leaving O’Malley dizzy. Just as quickly, any liveliness in O’Donnell’s expression also disappeared, leaving behind empty blue eyes in a blank face.

Jill Leary also seemed disturbed. She waited, as if hoping for more, but the newcomer had returned to staring at the table. “As you wish, O’Donnell, for now at any rate.”

†

Arkadia O’Malley had learned to float on prison routine as a ship might float on a rhythmic sea. She worked in the library, such as it was with its motley assortment of donated books, and it was not a location that was very often frequented. A variety of bizarre rumors had once been whispered about her, like the one that said she was a Russian spy who had assassinated a bishop. Some of the older officers remembered when the mystery of the woman had been a challenge, but all attempts to solve her had been in vain, and after a while Arkadia O’Malley simply became a prison oddity. A fixture. A cipher. The rumors still made their rounds, but they now excited no more interest than would an odd keepsake acquired by a seafaring uncle in his youth. Arkadia O’Malley had taken Hamlet’s boast to heart for close to two decades: she was bounded by a nutshell, but she had made herself ruler of infinite space. She was as anonymous as someone could be in a prison. Unfailingly polite, answering whenever spoken to, O’Malley rarely initiated or extended contact outside the library.

That was before Geraldine O’Donnell arrived at Armagh.

In the days that followed O’Donnell’s arrival and Leary’s surprise visit to the general population, O’Malley kept her usual distance, watching and listening. Rumors accompanied every new arrival, but the story, when sorted out, was simple on the surface. O’Donnell was on remand, with no trial scheduled. The American had been a tourist, it seemed, driving through the countryside with two companions. When they were stopped at a British roadblock, their rented car was searched and contraband was discovered, and it had not been drugs. Liz had been right; the car had carried guns or explosives, and during a scuffle with the soldiers, gunfire killed O’Donnell’s two companions.

There would be more to it than that. Something more was needed to account for the despair that enveloped the young American. O’Malley had not made peace with her imprisonment by entangling herself in the lives of Armagh’s inmates, and over the years she had tended her distance like another might tend a garden. Only during the clashes of the no-wash and hunger strikes that turned the entire prison into a battleground, drawing stark lines between prisoners as well as between the officials and the IRA, only then had O’Malley found it difficult to remain aloof.

In what became known as the Dirty Protest, the IRA men held at Long Kesh demanded status as prisoners of war and refused to wear uniforms that would mark them as common criminals. Led by Jill Leary and Mairead Farrell, the IRA women at Armagh supported the men, and soon the Rah inmates at both prisons were engaged in a fierce conflict with British authorities. When guards refused to let the women empty their chamber pots, they smeared the contents over the cell walls.

Armagh was an old prison and stink was everywhere even at the best of times. Whether or not they could actually smell the cells of the Dirty Protest, the other prisoners were united in their disgust. Arkadia O’Malley knew it was more than the smell; the protesters were offending against the very basic notion that women were supposed to uphold standards, especially those of decency. With a word here and a comment there, Arkadia O’Malley inserted her own position into the general chatter.

“It might smell bad,” she would say, “but wasn’t it clever to find a way to continue to fight even after they’d been counted out?” Farrell and her group had found a way to turn the prison itself into a battleground, and they fought with their bodies, as soldiers always did.

Their struggle was not O’Malley’s, but her heart had ached for the conditions the IRA women endured. Mairead Farrell and Jill Leary had started on the hunger strike along with Bobby Sands and the men at the Maze until they were ordered to stop. When the government of Iron Maggie gave way to the IRA demands, O’Malley felt as if she, too, had won a victory, a feeling shared across Ulster and beyond. The hunger strike had done more for The Cause than any pitched battle, showing the entire world the courage of the rebels pitted against the intransigence of Maggie Thatcher and her gang.

Geraldine O’Donnell was a different matter, and O’Malley didn’t understand why she was drawn to the new prisoner. The American would not be the first or last to arrive in the clutch of depression; in fact, this was a perfectly sensible response to finding oneself in prison. Depression could be the mind’s way of fitting a personality to her new circumstances. Speculating about just what had brought O’Donnell to Armagh, O’Malley remembered Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol with its plaintive refrain: “Each man kills the thing he loves.” O’Malley could not forget the flash of recognition that had shaken her when she first saw the new prisoner’s face.

†

Days passed. Weeks. A month. Geraldine O’Donnell went through the motions of adjustment, a heavy sluggishness signifying her continued depression. She ate little, spoke less. Some prisoners tried to make contact, but they might as well not have bothered. Jill Leary returned, but got no more joy of it than she had on her first visit. The prison rumor mill now reported that Geraldine had been in Ulster on vacation when she had fallen out with the law, that she had been studying in England, at Oxford.

“They say she was studying motorways,” Liz told Rosie.

“Not motorways, you silly git. She was a Rhodes Scholar. That’s different.”

“And what makes motorways different from roads?” But Liz was taking the piss, and Rosie knew it.

The day that Mattie Malloy went for O’Donnell, Arkadia O’Malley was present. Mattie Malloy was a prison type that came and went at Armagh with unfortunate regularity. She was a bully who claimed status by terrorizing the meek and the weak, especially loners. She worked at her reputation for brutality, and picked up minions who admired her bluff and swagger. Even women who weren’t particularly afraid of her didn’t challenge her either; prison was not known for generating altruism.

It was only a matter of time until Mattie decided that Geraldine was an outsider whom the herd would allow to be culled. On the way to evening meal, when the guards weren’t near, Malloy chose her moment.

“Wha’cher do that for?” Malloy snarled as she deliberately bumped into the American.

O’Donnell had her on height, but Mattie was a solid bull of a woman. She pushed Geraldine out of line. The chosen victim stared blankly and then tried to step around. Mattie blocked her. O’Donnell simply stopped, becoming the equivalent of a rag doll, an empty space. This way of disappearing was not an altogether absurd defense, but only if the aggressor was not determined to push the issue.

Arkadia O’Malley was watching, and she wondered if, in her depression, Geraldine might even wish for the pain that Mattie was threatening.

The guards were preoccupied elsewhere, but the dining room was watching.

Mattie Malloy struck, a ham-fisted blow aimed for the midriff that could have stunned an ox. Malloy’s anger was always on a hair trigger, and something about O’Donnell had roused her to the point that she meant to do real harm. But the blow never connected. Geraldine caught the hand aimed at her and held it, just held it, as if Malloy’s strength were nothing. Blank eyes lost their habitual emptiness and focused on Mattie.

Arkadia O’Malley was close enough to see the look that Mattie saw, a look that bespoke murder. Anger at last animated O’Donnell’s features, an anger that, now awakened, clearly hoped for more action. Mattie Malloy, the bully, realized that she had seriously miscalculated and backed away. The encounter began and ended so quickly that very few watchers even realized that anything had happened. Arkadia O’Malley had been watching, and in that moment believed that it might just be possible that Geraldine had been sent to Armagh for good and righteous reasons.

“Did you see that?” Liz asked Rosie.

“I’m not blind. I thought my sister was getting it wrong, what she was telling me last visit. She read in the papers that O’Donnell’s from this part of Boston in Americay where the Irish go. They make them tough there, she says.”

That night, Arkadia O’Malley was reminded that Hamlet had said he could be content in a nutshell were it not for bad dreams.

The dream wasn’t exactly bad, in the sense of nightmarish, and in fact it began quite pleasantly. O’Malley had lately been re-reading Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. The lengthy poem had a certain repetitive beat that slipped easily into prison life, but O’Malley read it primarily for the vivid images that often stayed to populate her dreams. She had trained herself to hold a level of consciousness during dreaming, and she immediately recognized Britomart when Spenser’s lady knight came riding out of the mists. She herself, an old woman leaning on a staff, seemed to be located in a forest glade when the lady knight appeared. Britomart rode a gray horse, her bright helm dazzling, one hand resting on her sheathed sword. Her long dark hair flowed over silver armor with a collar that was studded with red, yellow, and green gems. A blue gem gleamed from the pommel of the sword encased in a silver sheath inlaid with gold.

“Have you seen my garland?” Britomart asked.

The old crone looked across the glade to a tree on which the flowery garland hung: marigold and chamomile, poppy and periwinkle, lilac, rose and jasmine.

“There is your garland.” Even as she spoke, she saw the garland grow a dainty hoof in each quarter and when the feet had formed, the garland leapt from the tree and left faster than mortal horse could gallop.

The crone looked again to Britomart, and the sight was like to break her heart. The dazzling figure had lost all beauty. Her armor was dented and streaked with tarnish. The gems had disappeared from their settings. The horse was gone. The woman’s hair was wild and tangled and she had no helm, only a broken sword, but her face was worst of all. There was no doubt to whom the features, so downcast and lost, belonged.

“Where is my garland? Help me find and keep her,” pleaded Geraldine.

Arkadia O’Malley woke into the prison darkness of stone walls, and the colors of her imagination fled back to the harbor of her soul. She lay awake, committing the dream’s images to her waking memory. Such dreams came in their own time, and she considered it part of her work to prepare herself for such visitations. She recognized the importance of this one by the intensity of the emotions it evoked. Still full of feeling, she wanted to weep and, at the same time, to sing and bless her life.

When the feelings subsided, and when she was sure she had remembered every detail so that it wouldn’t disappear with daylight, O’Malley began to wonder at the meaning of the dream’s imagery. Obviously, Geraldine O’Donnell was Britomart, and she had lost something precious. There were many things that might signify: her freedom, her identity, her life’s purpose. Arkadia O’Malley was supposed to help her find her four-footed “garland”. O’Malley might have thought the garland was a woman, except that having four legs implied something other than human. Still, Geraldine had wanted to keep “her”. The absurdity of the notion of a four-footed garland kept nagging O’Malley until suddenly, in the darkness, she smiled and nearly laughed aloud.

She gave Freud his due for demystifying many secrets of the dream, but she also knew that one should never underestimate the mind’s love of punning. The garland was “forfeited”. That came from The Faerie Queene, a reasonable setting considering O’Malley’s daytime reading. Britomart was one of the heroes who still pursued the “goodly usage of those antique tymes, In which the sword was servaunt unto right.” The lady knight’s terrible sorrow was for a lost life that might already be forfeited.

†

“Well, would you look at that!” Rosie jabbed Liz with her elbow, a large gesture, as unusual as a shout would have been.

“Jesus, Mary, and Joseph!”

Liz and Rosie had grown so used to the quiet presence of Arkadia O’Malley sitting near them at meals that any change in her behavior might have roused them to comment, but their surprise was because the prison’s resident mysterious inmate had just taken a seat at the table with the prison’s most recent focus of gossip. Liz and Rosie weren’t the only two in the dining room who were watching.

Nothing happened. Neither the American nor the Irish woman was given to talking, so even if it was disappointing to the rest of the population, it was not surprising that the two ate in silence. In fact, it wasn’t until several meals had passed in silence and no one was giving any notice to the odd pairing that one of them spoke.

“I have a book for you,” Arkadia O’Malley said in a tone that had, once upon a time, made her listeners determined to read quickly and attentively.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.